The 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the United States. The Senate passed the amendment in April 1864, settling on language with bipartisan appeal. The House then rejected it. Following battlefield victories and Lincoln’s reelection, Congress reconsidered, approving it in January 1865. It was ratified December 6, 1865.

Special thanks to Kurt Lash from the University of Richmond School of Law for sharing his research and expertise. Kurt Lash, The Reconstruction Amendments: Essential Documents (University of Chicago Press, 2019).

Turn device horizontally for easier scrolling.

Event — July 13, 1787

Event — January 1, 1808

Event — November 6, 1860

Event — August 6, 1861

Event — January 1, 1863

Event — November 19, 1863

Draft — December 14, 1863

Draft — December 14, 1863

Event — December 14, 1863

Draft — January 11, 1864

Event — January 11, 1864

Draft — February 8, 1864

Event — April 4, 1864

Event — April 8, 1864

Event — June 8, 1864

Event — June 15, 1864

Event — September 2, 1864

Event — November 8, 1864

Event — January 6, 1865

Draft — January 31, 1865

Event — January 31, 1865

Event — April 9, 1865

Event — December 6, 1865

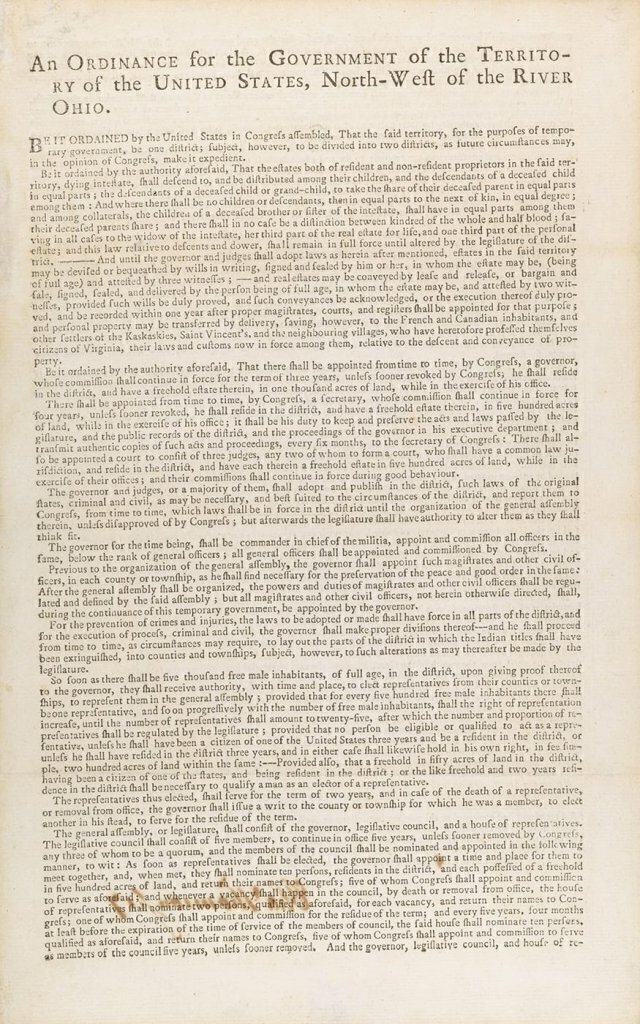

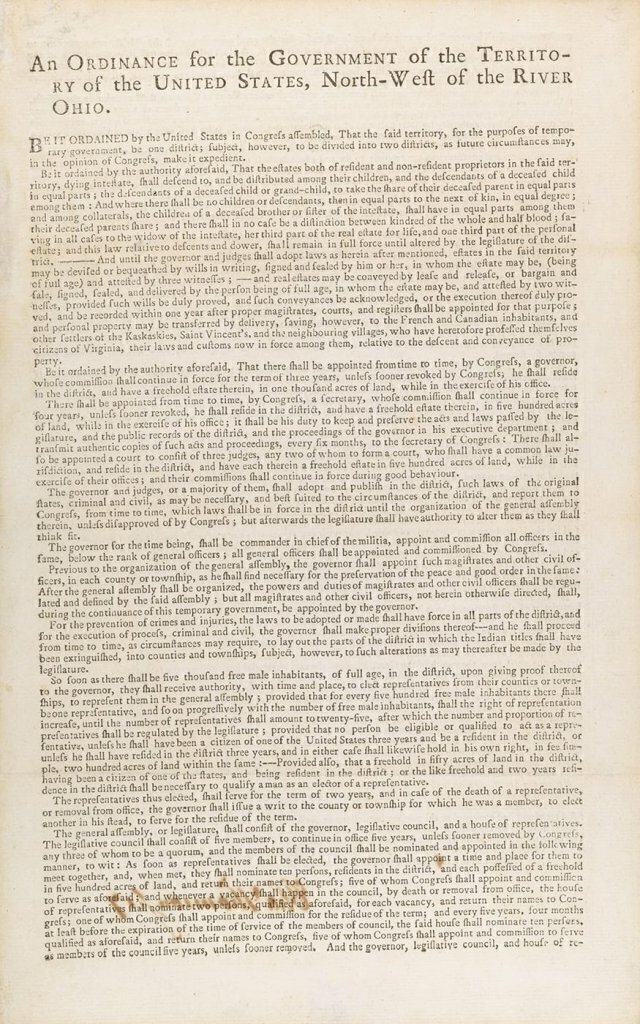

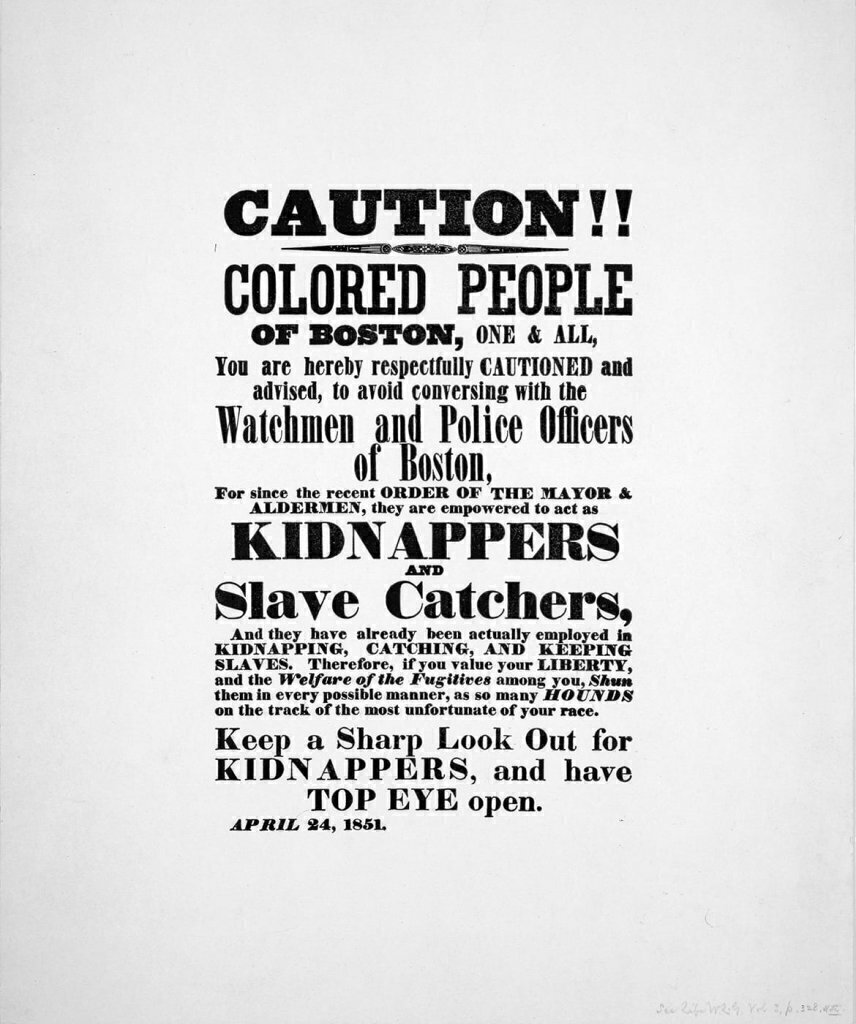

This congressional act established a framework for creating new states in the Northwest Territory and protecting the civil liberties of settlers. It banned slavery in the territory but also provided for the recapture of fugitive slaves.

Congress passed a law in 1807 to ban “the importation of slaves into any port or place within the jurisdiction of the United States” beginning on January 1, 1808. This was the earliest that the Constitution permitted Congress to impose such a ban.

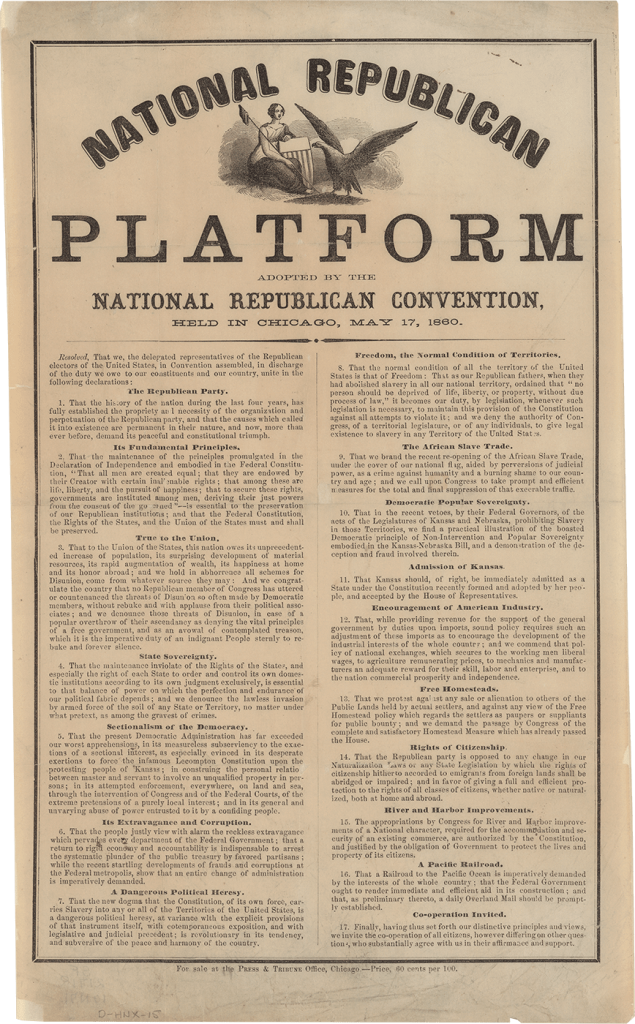

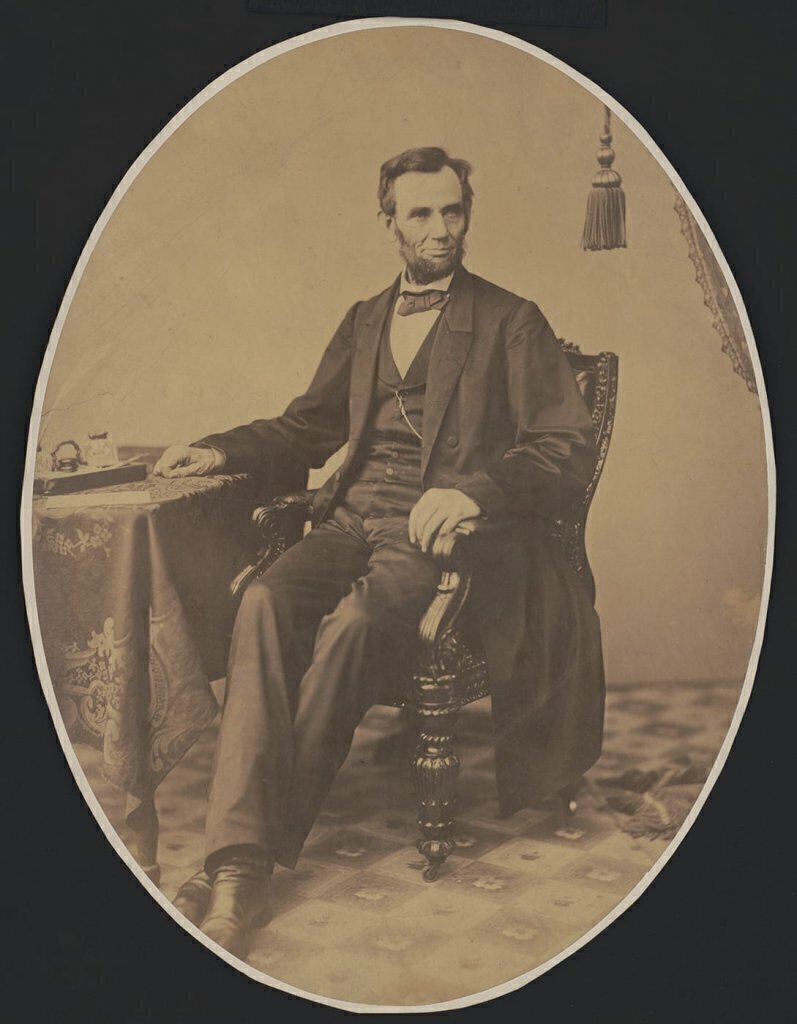

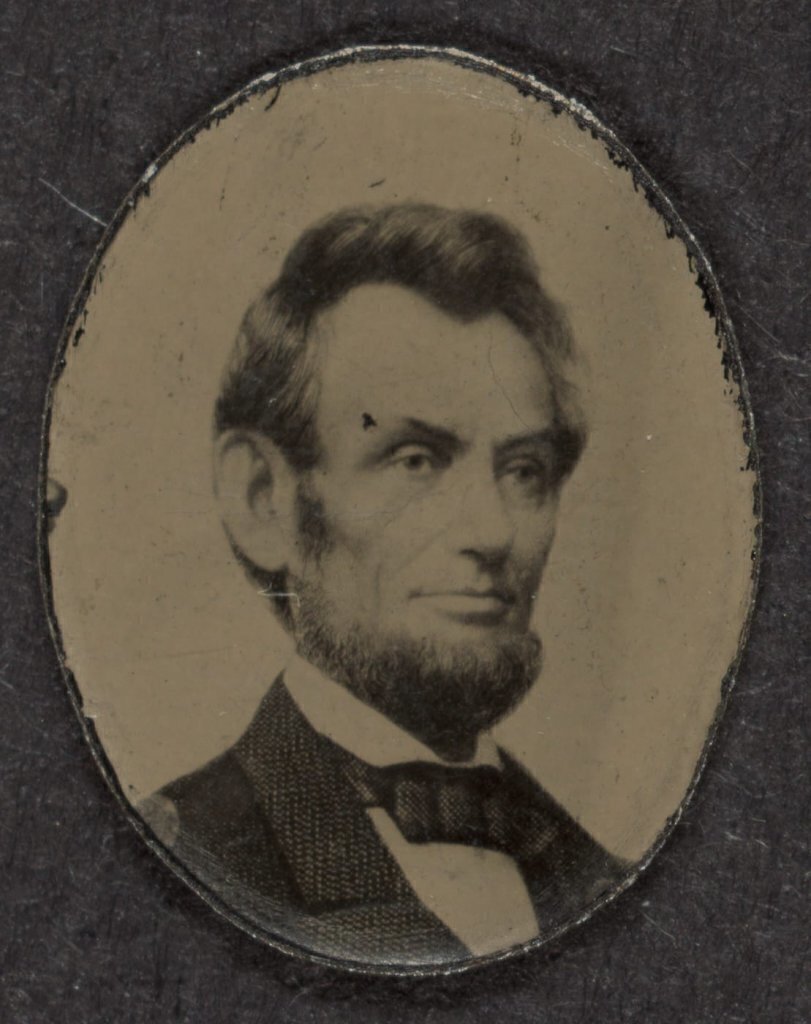

November 6, 1860

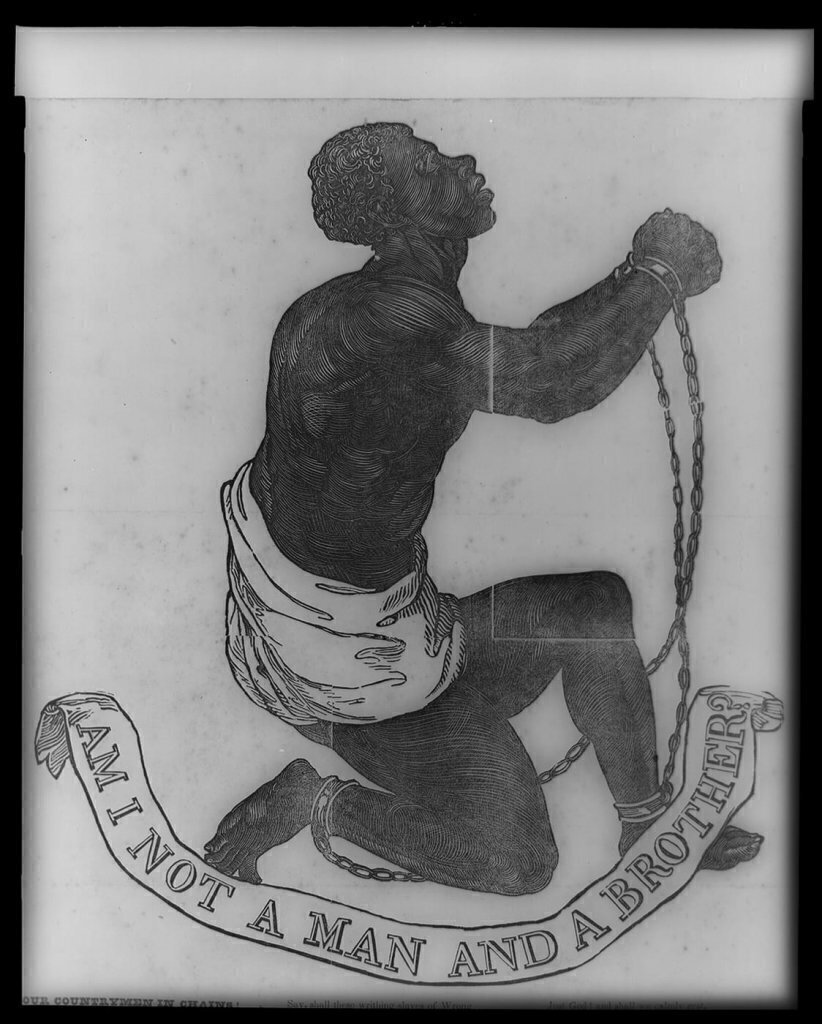

Republican Abraham Lincoln won the election, becoming the nation's first anti-slavery president. Soon after, slaveholding states started to break away from the United States. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, sparking the Civil War.

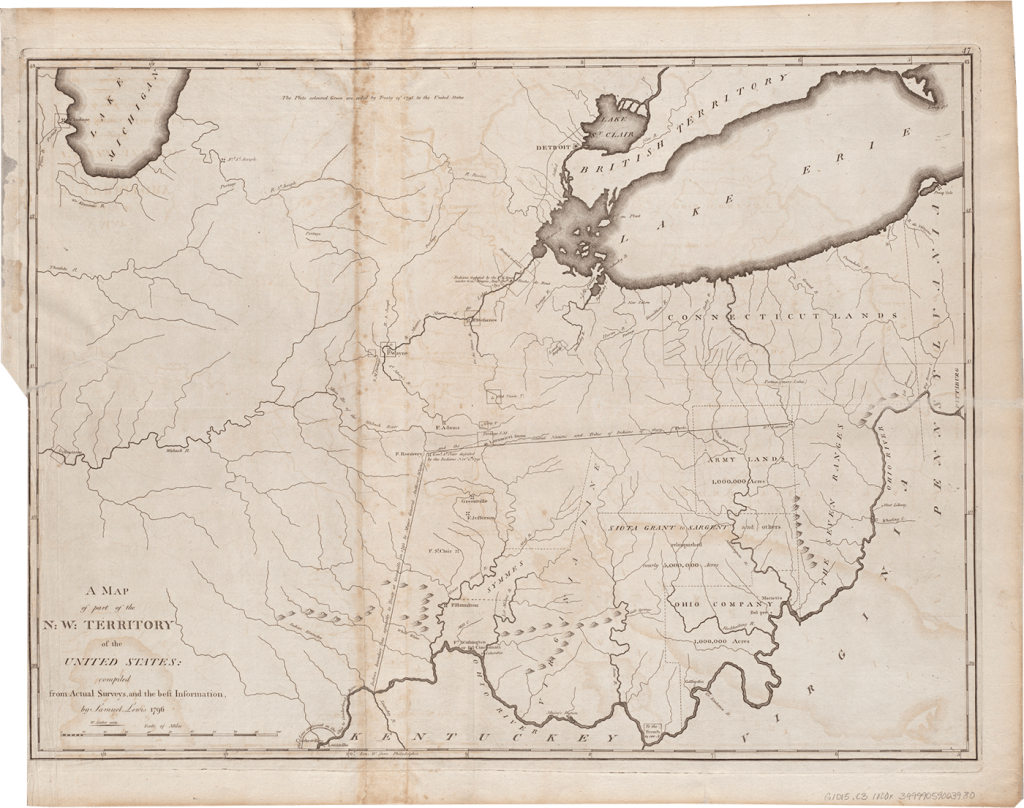

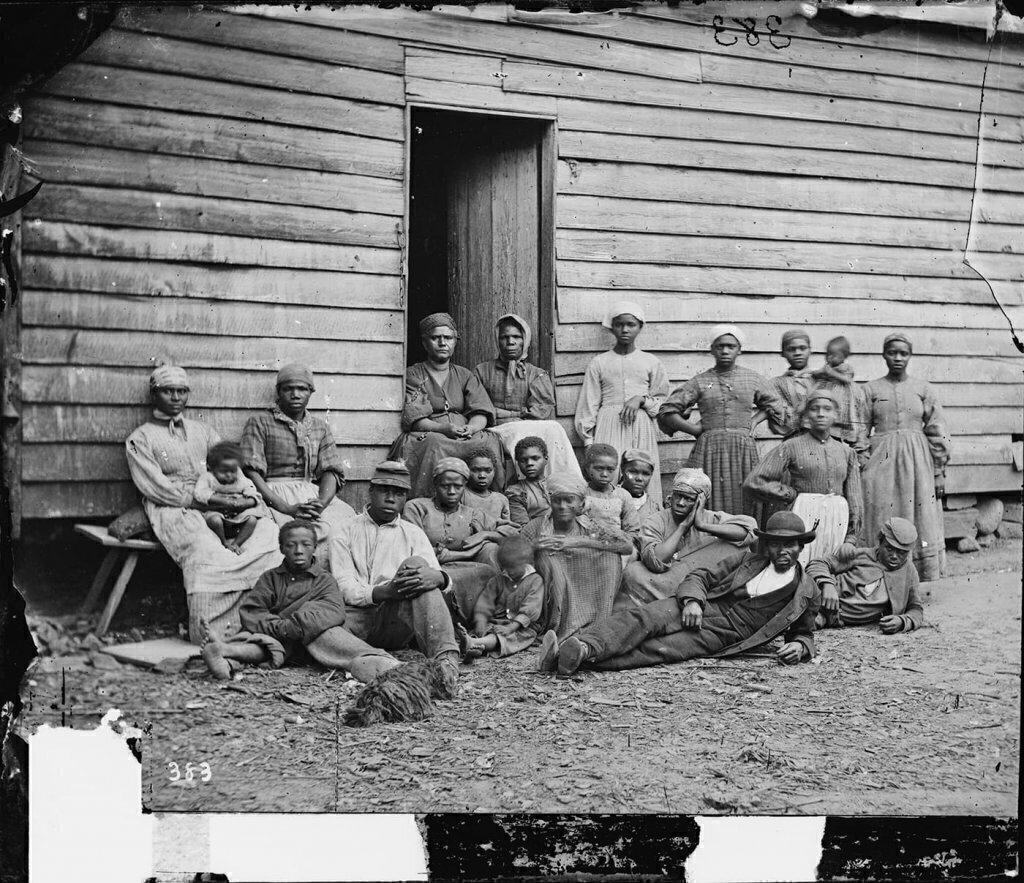

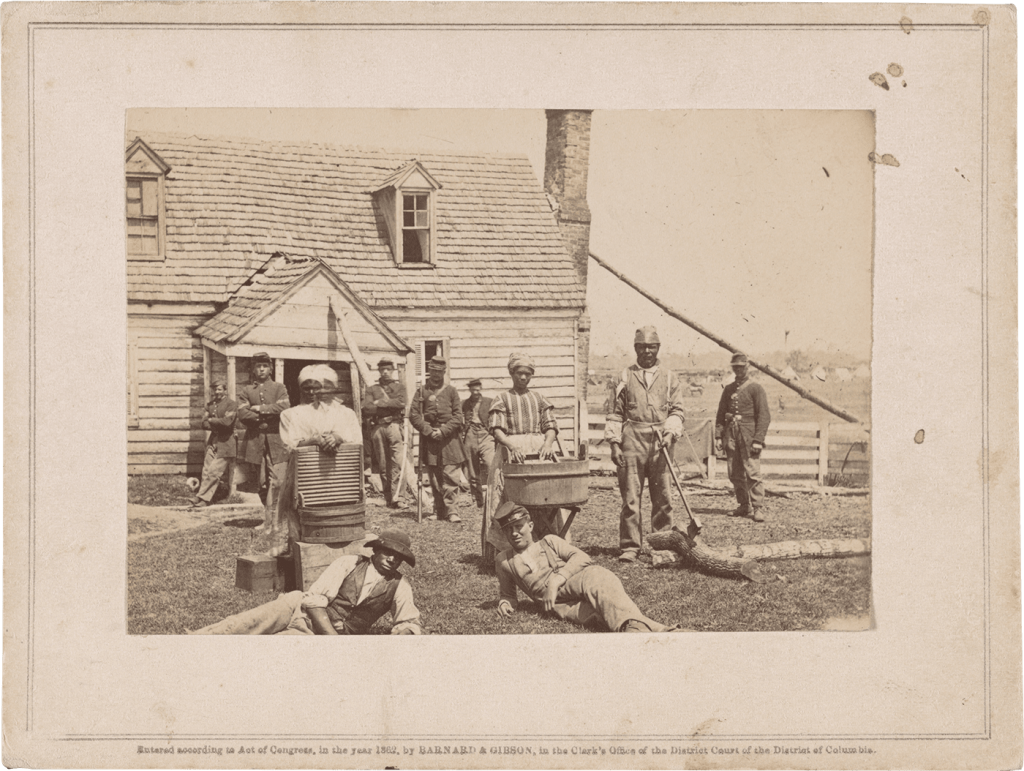

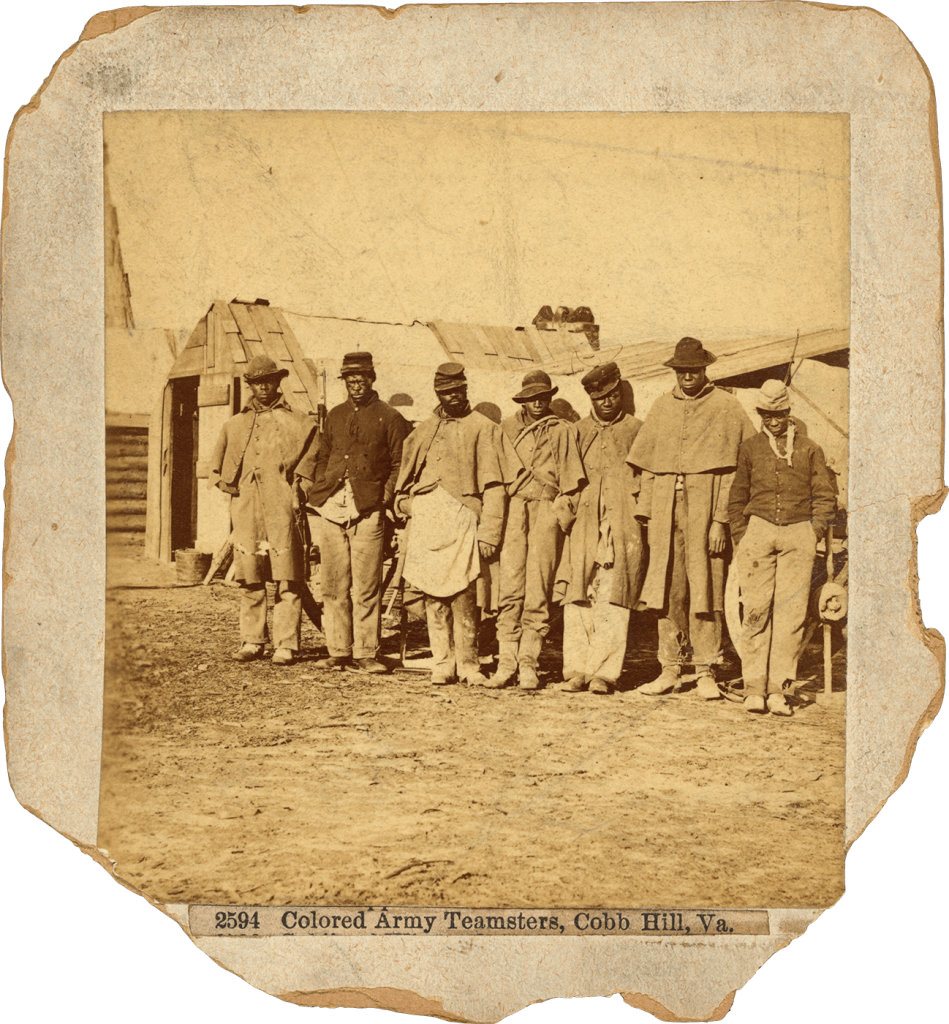

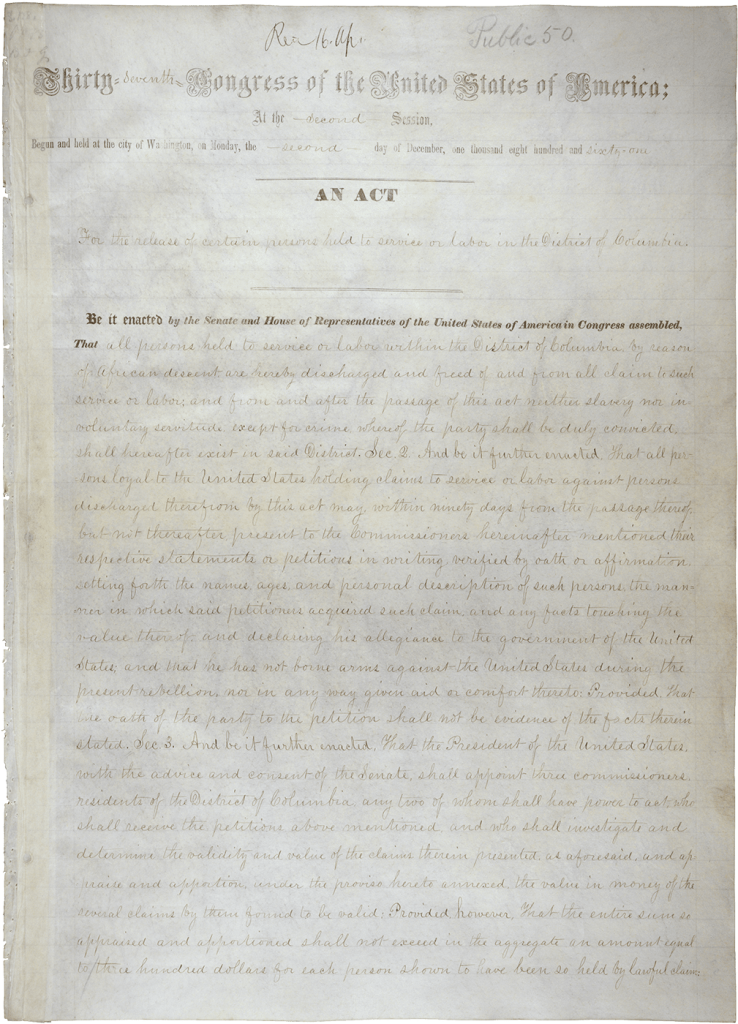

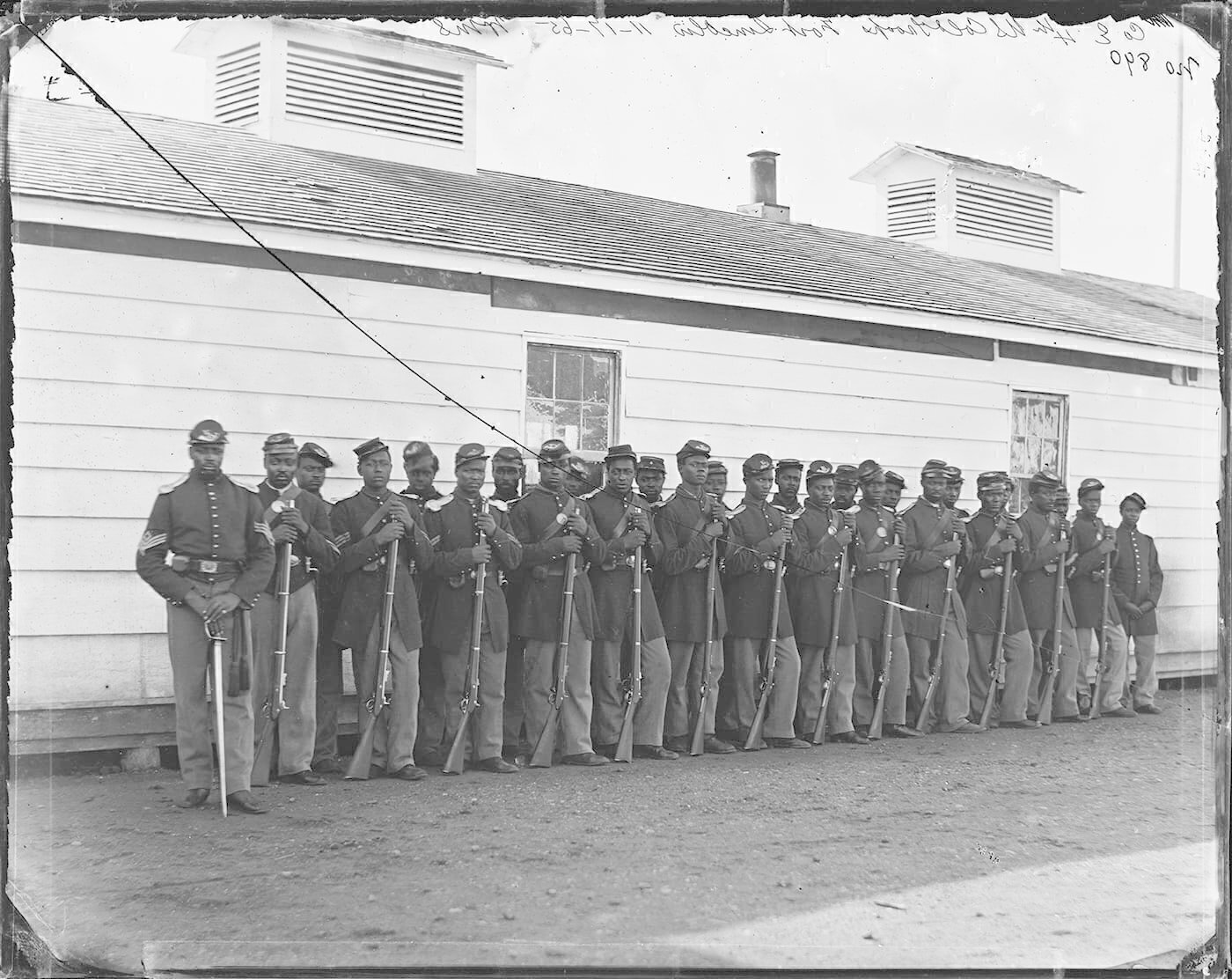

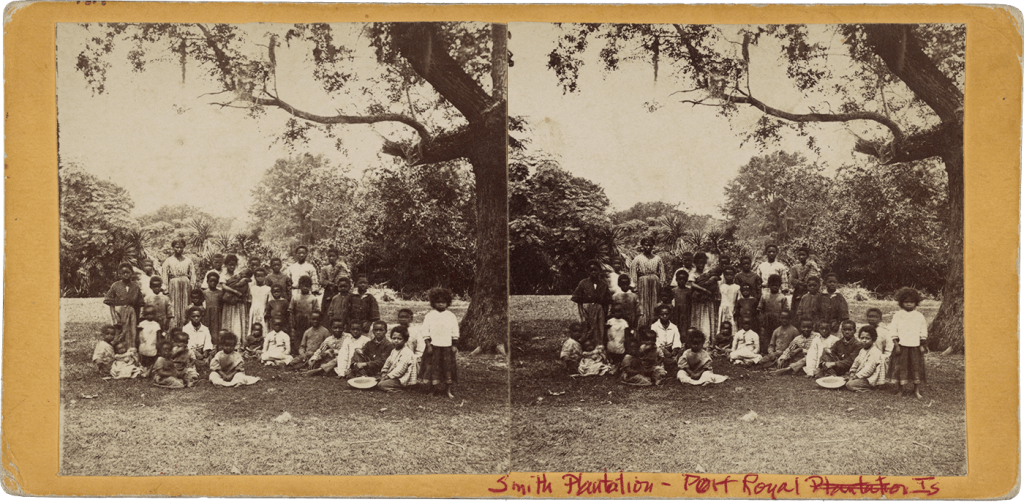

In 1861 and 1862, Congress passed a series of laws that attacked slavery. Across the South, enslaved people were coming into the lines of the U.S. Army and Navy, seeking freedom. One set of laws diminished slave owners' legal claims on those people. The other set abolished slavery in Washington, D.C., and the federal territories.

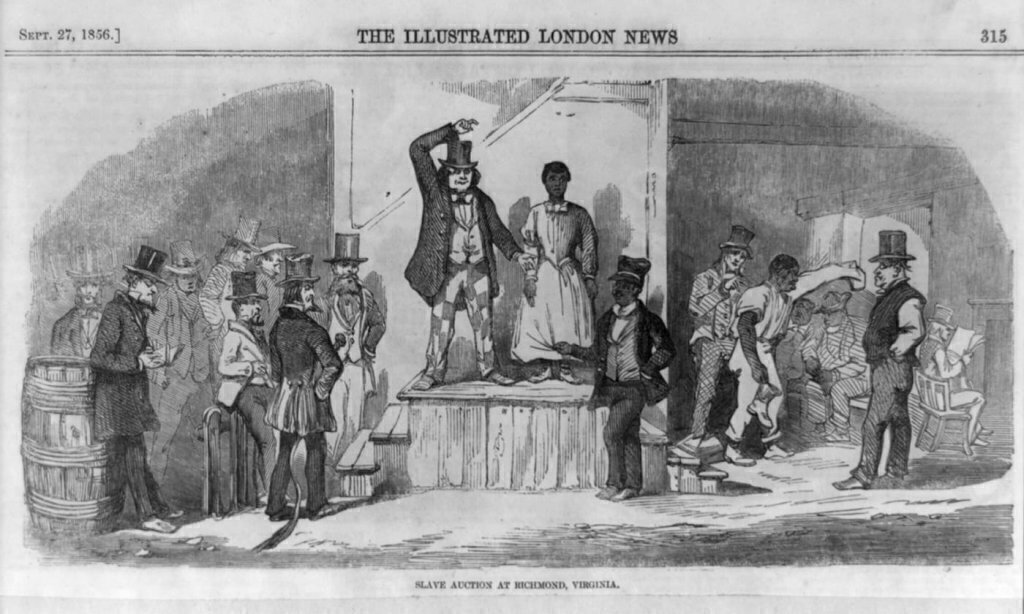

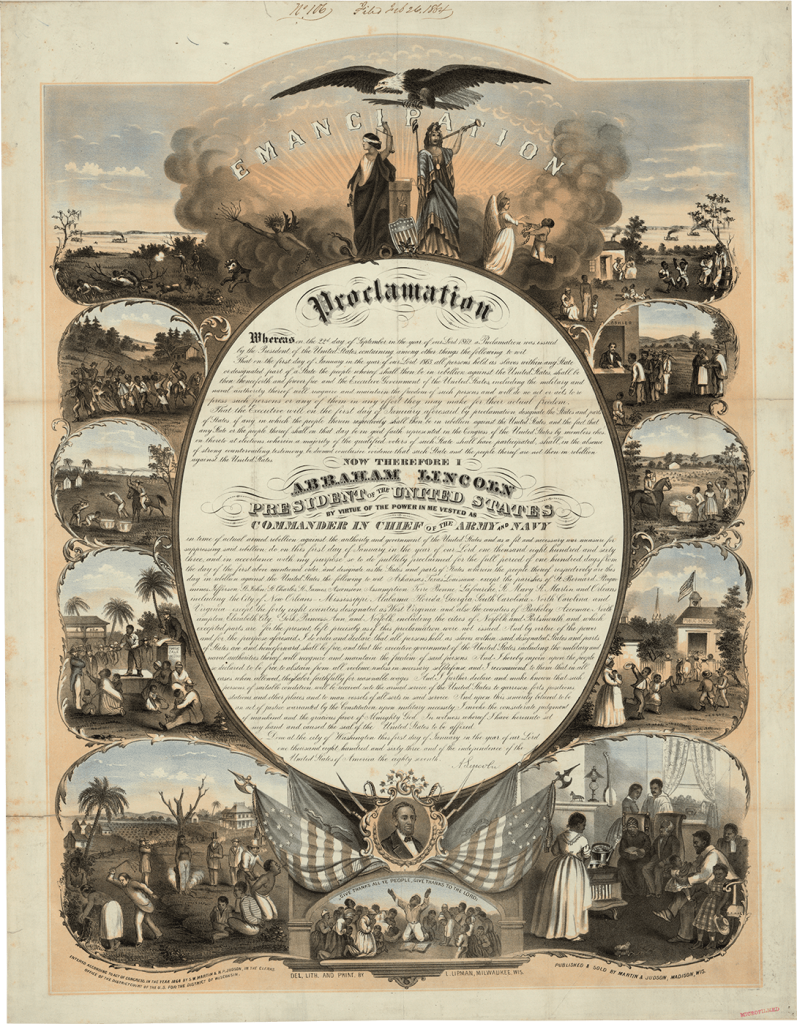

Abraham Lincoln used his presidential war powers to declare slavery abolished in areas under rebellion. The Emancipation Proclamation promised freedom to around 3.2 million slaves, but only a constitutional amendment would finally settle the issue of slavery.

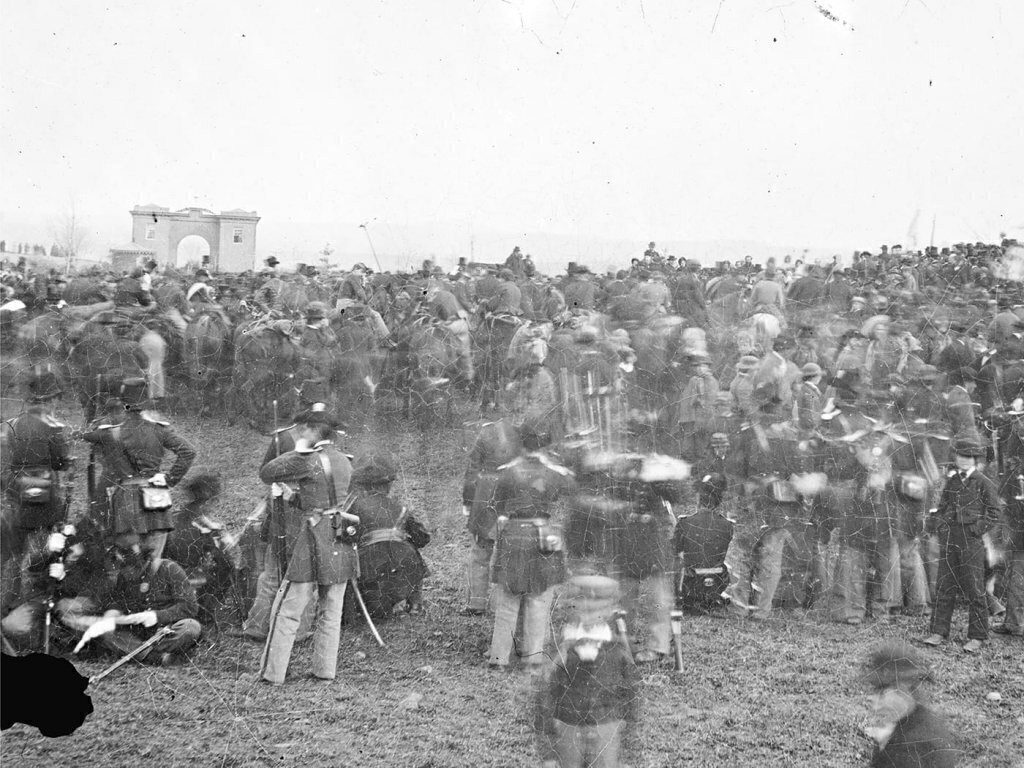

November 19, 1863

At the dedication of Gettysburg's National Cemetery, Lincoln embraced the Declaration of Independence, recalling how the nation was “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” By resurrecting these promises, Lincoln committed post-war America to “a new birth of freedom.”

December 14, 1863

This draft prohibited slavery and explicitly empowered Congress. Although it was similar to the final amendment, it included language arguing that slavery was inconsistent with the principles of free government.

December 14, 1863

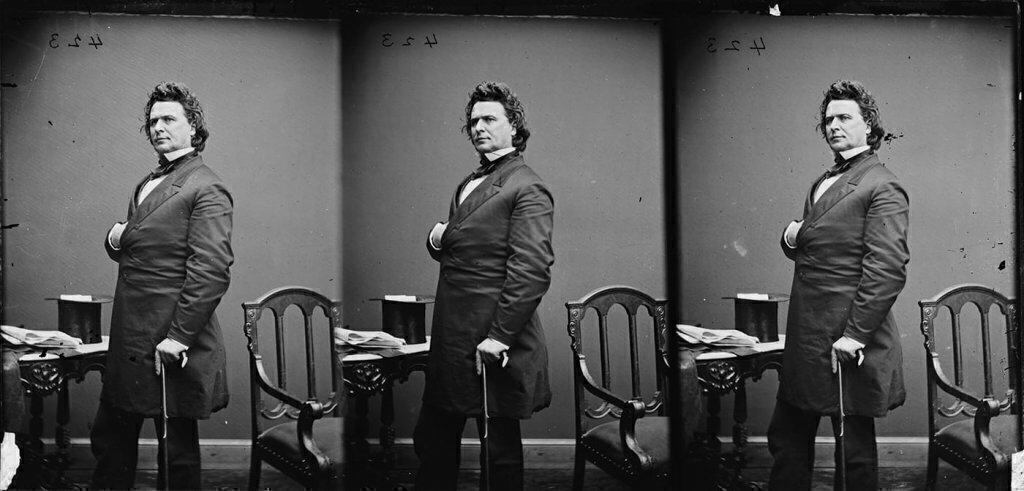

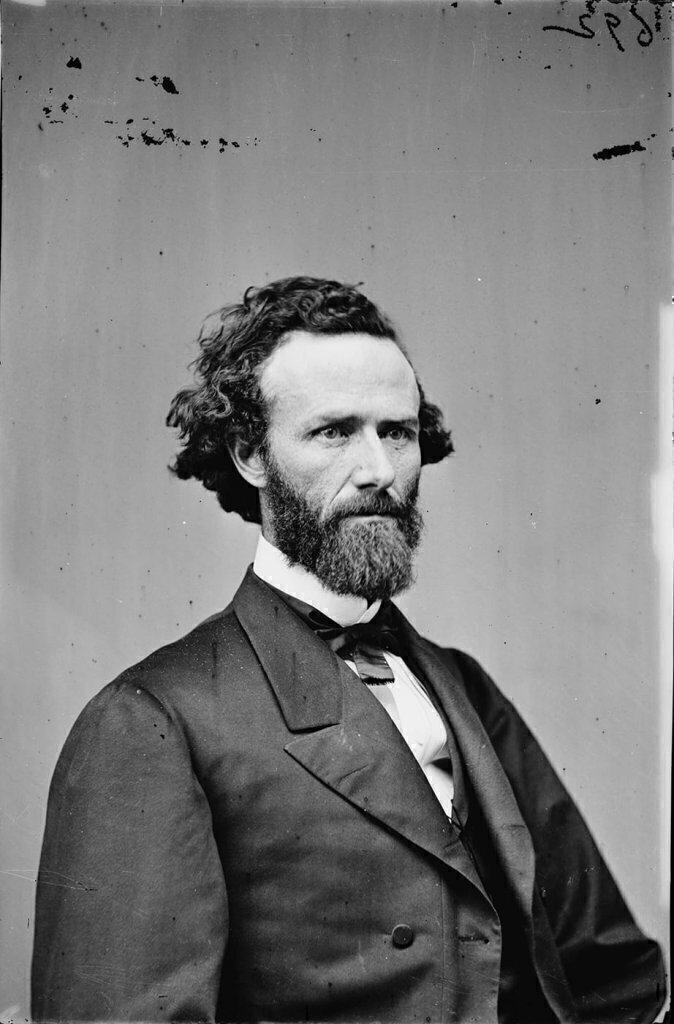

James F. Wilson

U.S. Representative, Republican, Iowa

Slavery, being incompatible with a free government, is forever prohibited in the United States; This draft expressed a central Republican critique of slavery: That it was “incompatible with a free government.” By abolishing slavery, the Republicans sought to realize the Declaration of Independence's promise of freedom. and involuntary servitude shall be permitted only as a punishment for crime. This language was derived from the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, which allowed involuntary servitude to be used as a punishment for crime. Congress shall have power to enforce the foregoing section of this article by appropriate legislation. This clause empowered Congress to pass laws attacking slavery. Previous amendments limited national power. This one would empower the national government—a key innovation adopted by the final text and followed by future amendments.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.December 14, 1863

James F. Wilson

U.S. Representative, Republican, Iowa

Slavery, being incompatible with a free government, is forever prohibited in the United States; This draft expressed a central Republican critique of slavery: That it was “incompatible with a free government.” By abolishing slavery, the Republicans sought to realize the Declaration of Independence's promise of freedom. and involuntary servitude shall be permitted only as a punishment for crime. This language was derived from the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, which allowed involuntary servitude to be used as a punishment for crime. Congress shall have power to enforce the foregoing section of this article by appropriate legislation. This clause empowered Congress to pass laws attacking slavery. Previous amendments limited national power. This one would empower the national government—a key innovation adopted by the final text and followed by future amendments.

Select a Document

December 14, 1863

The language in Ashley's draft was close to the final amendment's text—except, it lacked a clause explicitly empowering Congress. Considered by the House Judiciary Committee and used to form the final text.

December 14, 1863

James Ashley

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

Slavery or involuntary servitude, This clause took aim at slavery. Ashley had long been one of the strongest anti-slavery voices in Congress. except in punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, This language was derived from the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, which allowed involuntary servitude to be used as a punishment for crime. is hereby forever prohibited in all the States of this Union, and in all Territories now owned, or which may hereafter be acquired by the United States. Republicans long argued “Freedom National, Slavery Local.” Congress could abolish slavery in federally controlled areas, but not in states where it already existed. With this clause, the Constitution would read: “Freedom National, Slavery Nowhere.”

Select highlighted text to view analysis.December 14, 1863

James Ashley

U.S. Representative, Republican, Ohio

Slavery or involuntary servitude, This clause took aim at slavery. Ashley had long been one of the strongest anti-slavery voices in Congress. except in punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, This language was derived from the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, which allowed involuntary servitude to be used as a punishment for crime. is hereby forever prohibited in all the States of this Union, and in all Territories now owned, or which may hereafter be acquired by the United States. Republicans long argued “Freedom National, Slavery Local.” Congress could abolish slavery in federally controlled areas, but not in states where it already existed. With this clause, the Constitution would read: “Freedom National, Slavery Nowhere.”

Select a Document

December 14, 1863

Two representatives—James Ashley and James Wilson—each introduced proposals for an abolition amendment, which were then sent to committee.

January 11, 1864

This draft was similar to the final text. However, it also proposed a change to Article V's amendment process, which would have made it easier to amend the Constitution. Submitted to the Senate Judiciary Committee for consideration. Then, two-thirds of both houses agreed to strike the part that would have changed the amendment process.

January 11, 1864

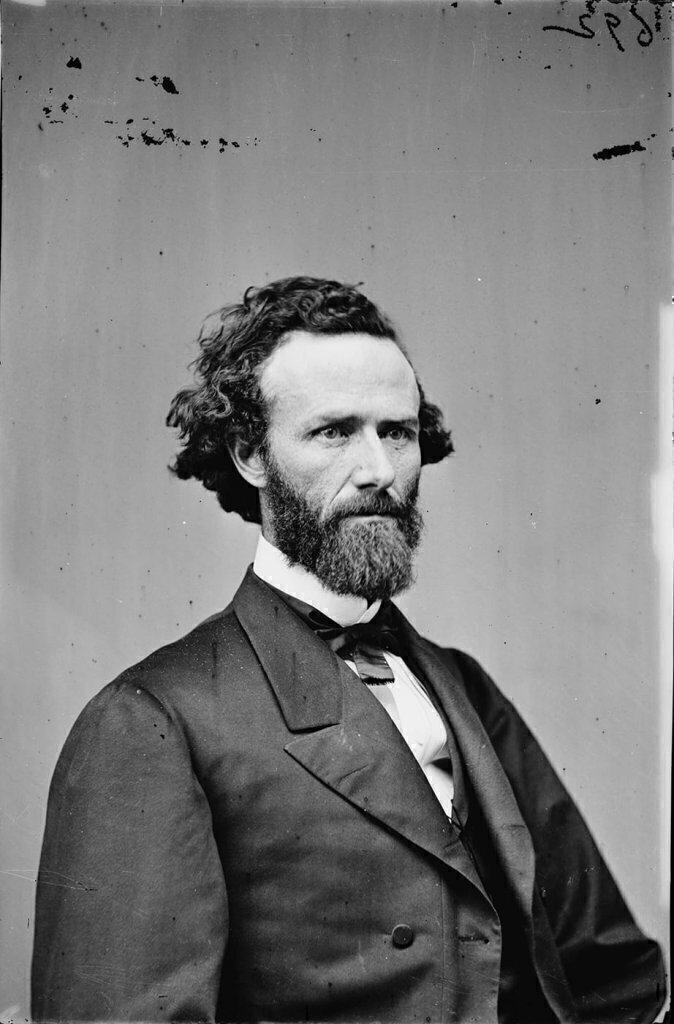

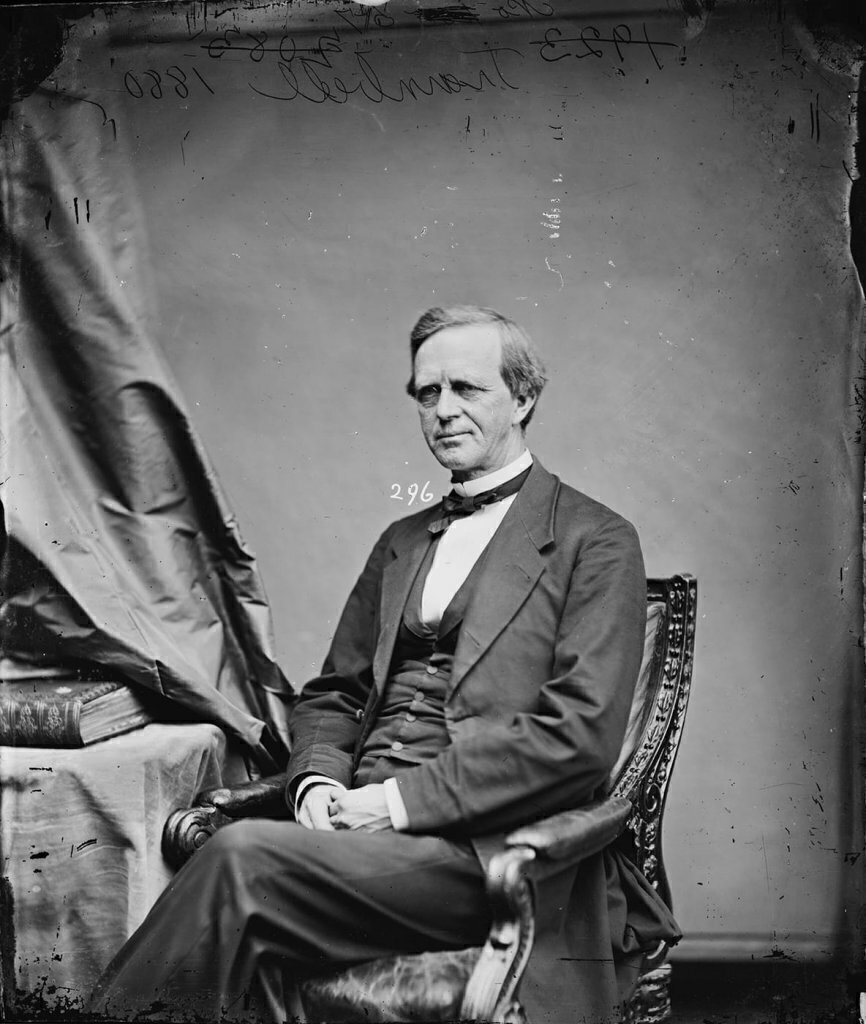

John Brooks Henderson

U.S. Senator, Republican, Missouri

Slavery or involuntary servitude, This clause took dead aim at the institution of slavery. except as a punishment for crime, shall not exist in the United States. This text made it clear that the amendment would eliminate slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States. The Congress, whenever a majority of the members elected to each House shall deem it necessary, may propose amendments to the Constitution, or, on the application of the Legislatures of a majority of the several States, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which in either case shall be valid, to all intents and purposes, as part of the Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, or by conventions in two thirds thereof; as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by Congress.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 11, 1864

John Brooks Henderson

U.S. Senator, Republican, Missouri

Slavery or involuntary servitude, This clause took dead aim at the institution of slavery. except as a punishment for crime, shall not exist in the United States. This text made it clear that the amendment would eliminate slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States. The Congress, whenever a majority of the members elected to each House shall deem it necessary, may propose amendments to the Constitution, or, on the application of the Legislatures of a majority of the several States, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which in either case shall be valid, to all intents and purposes, as part of the Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, or by conventions in two thirds thereof; as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by Congress.

Select a Document

January 11, 1864

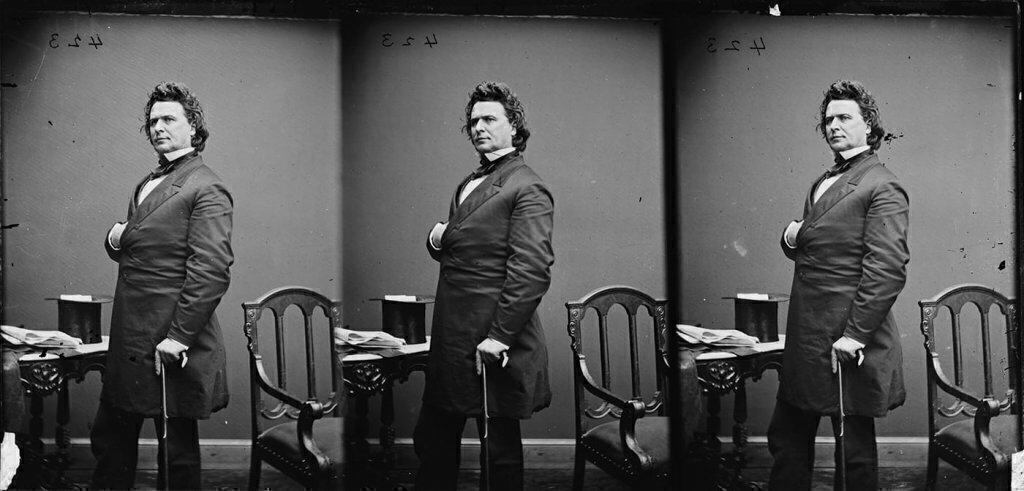

John Brooks Henderson—a key War Democrat and former slaveholder—proposed an abolition amendment in the Senate. Republicans sought to attract Democratic support, making it a bipartisan initiative.

February 8, 1864

This draft took a broad stance on equality, attempting to guarantee equal rights for all people within the United States. It also did not allow forced labor as a form of criminal punishment. Senator Lyman Trumbull, a moderate Republican, opposed Sumner's broad proposal. Sumner's proposal failed.

February 8, 1864

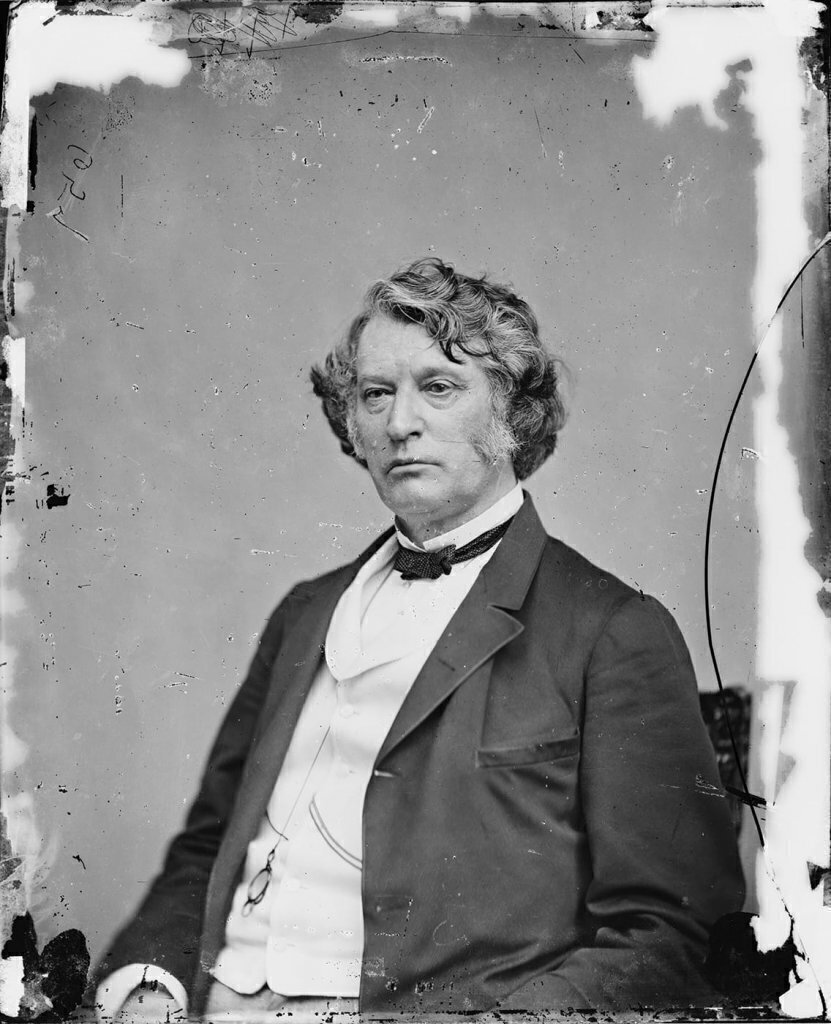

Charles Sumner

U.S. Senator, Republican, Massachusetts

Everywhere within the limits of the United States, and of each State or Territory thereof, Republicans long argued “Freedom National, Slavery Local.” Congress could abolish slavery in federally controlled areas, but not in states where it already existed. With this clause, the Constitution would read: “Freedom National, Slavery Nowhere.” all persons are equal before the law, so that no person can hold another as a slave. This language outlawed slavery with no exceptions for criminal punishment. This was contrary to other proposals, which drew on the 1787 Northwest Ordinance. This language also provided legal equality for all. Many Republicans feared that this language would turn off conservatives—including War Democrats. The 14th Amendment would echo this provision in the Equal Protection Clause.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.February 8, 1864

Charles Sumner

U.S. Senator, Republican, Massachusetts

Everywhere within the limits of the United States, and of each State or Territory thereof, Republicans long argued “Freedom National, Slavery Local.” Congress could abolish slavery in federally controlled areas, but not in states where it already existed. With this clause, the Constitution would read: “Freedom National, Slavery Nowhere.” all persons are equal before the law, so that no person can hold another as a slave. This language outlawed slavery with no exceptions for criminal punishment. This was contrary to other proposals, which drew on the 1787 Northwest Ordinance. This language also provided legal equality for all. Many Republicans feared that this language would turn off conservatives—including War Democrats. The 14th Amendment would echo this provision in the Equal Protection Clause.

Select a Document

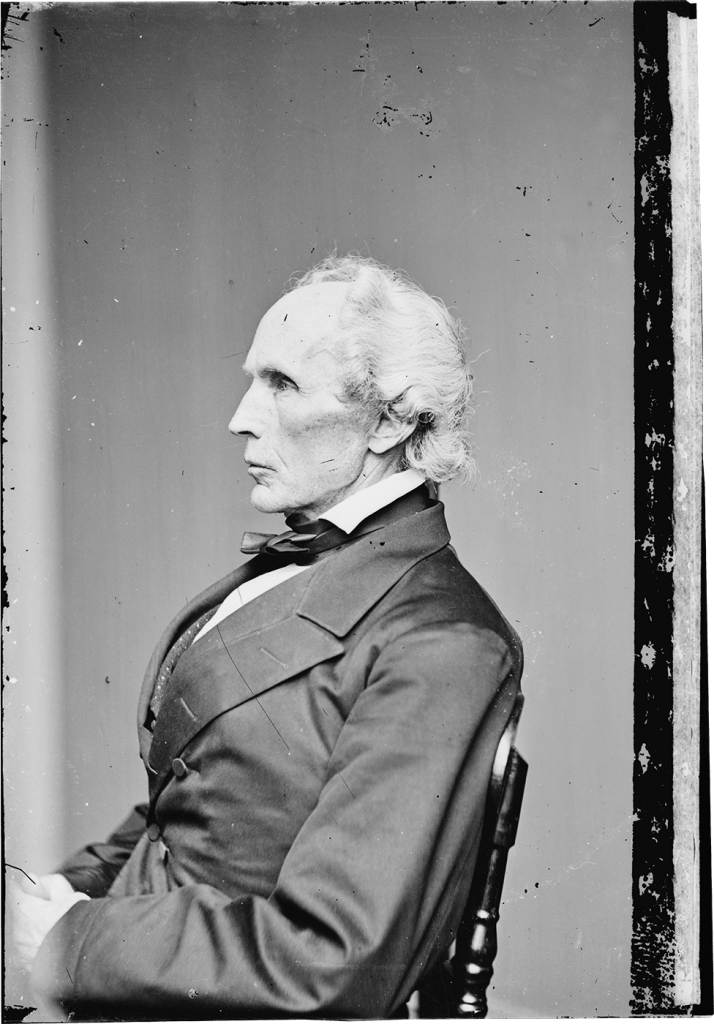

Senator Reverdy Johnson—a powerful Democrat from Maryland—delivered a pivotal speech supporting the amendment. He argued that “a prosperous and permanent peace can never be secured if [slavery] is permitted to survive.” This speech revealed growing support for abolition in the loyal border states.

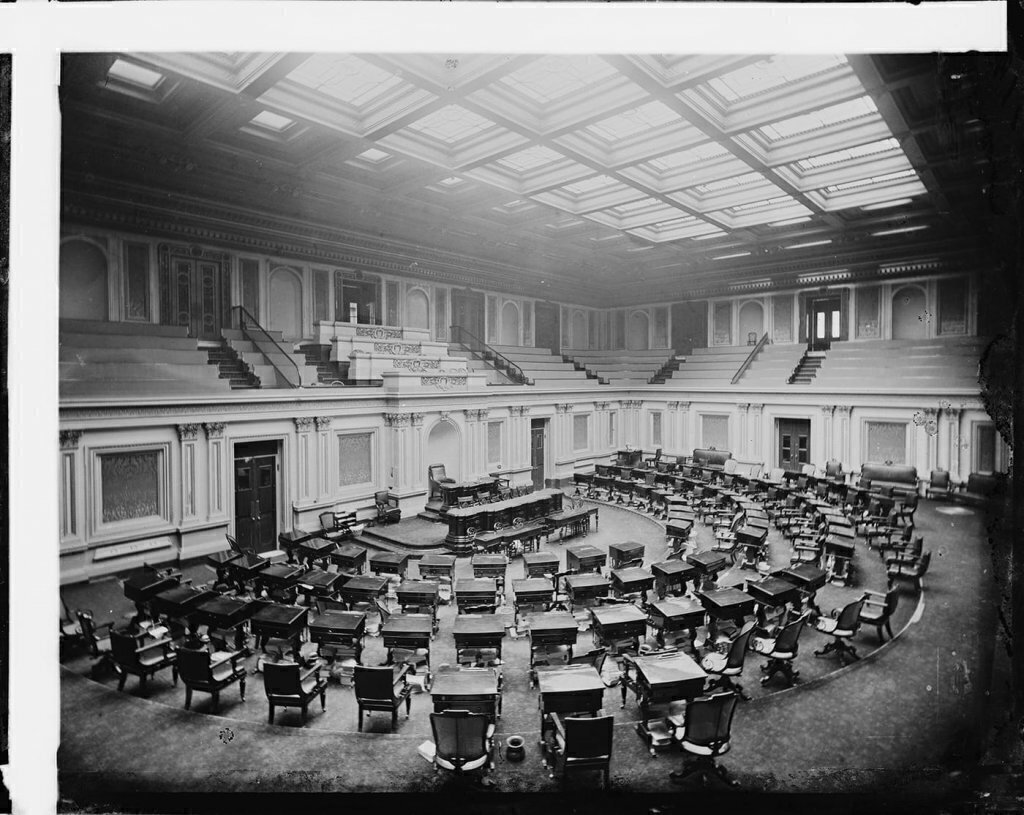

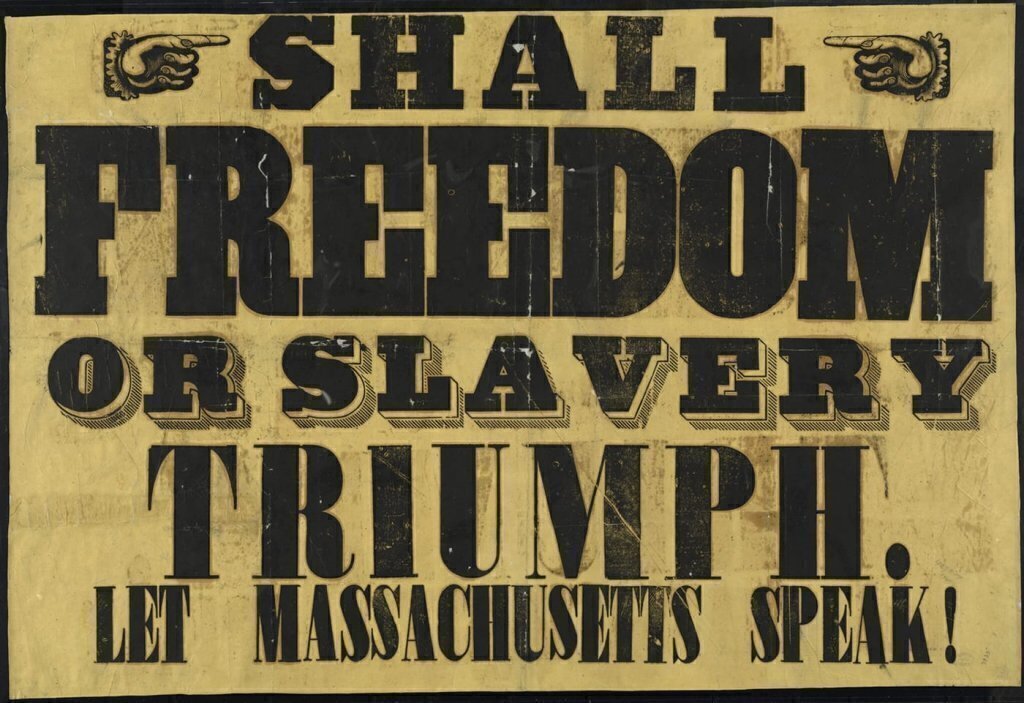

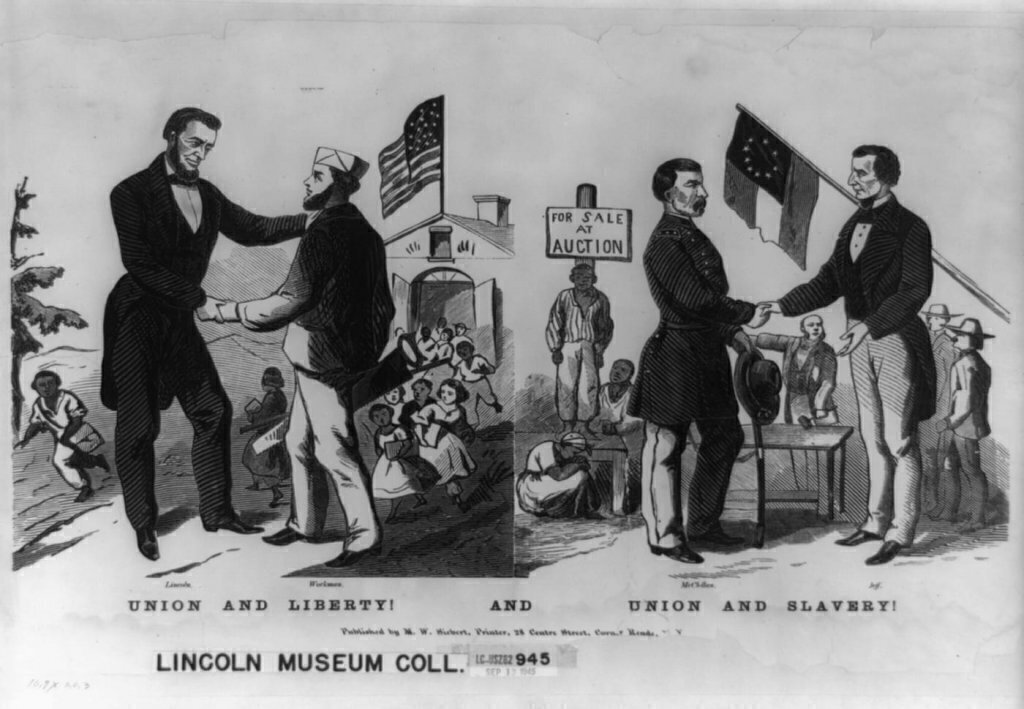

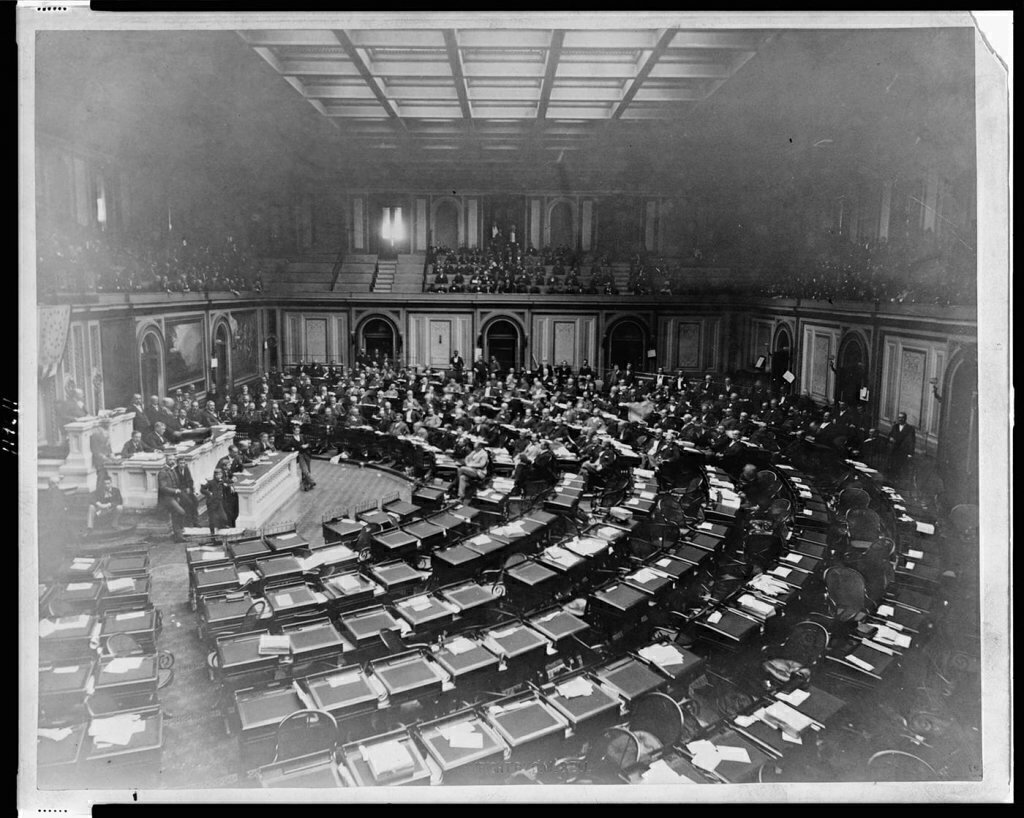

The Senate passed the abolition amendment on April 8, 1864. Although Charles Sumner's proposal failed, he argued that an abolition amendment would bring “the Constitution into avowed harmony with the Declaration of Independence.”

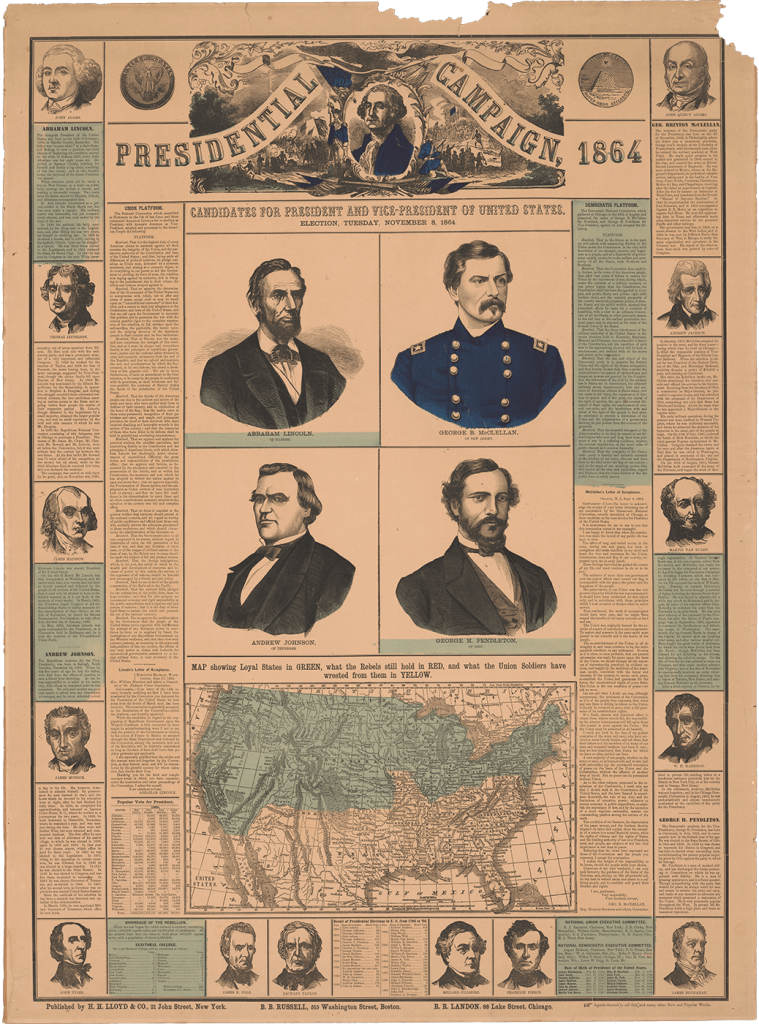

The Republican Party nominated Abraham Lincoln for a second presidential term.

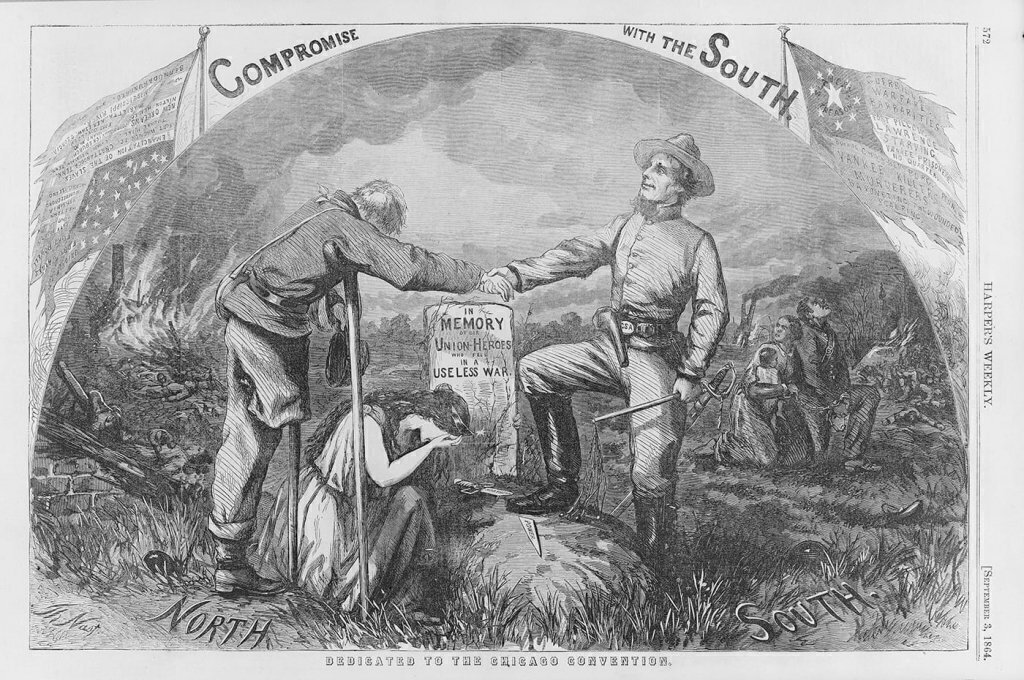

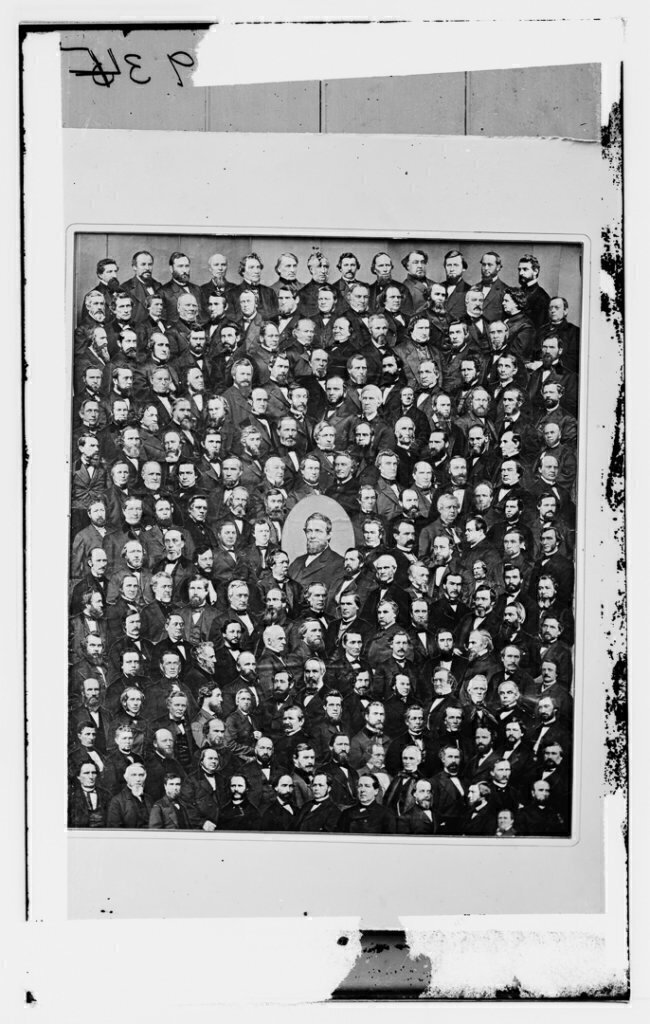

In June 1864, the House voted on the proposed amendment. It received a majority, but not the two-thirds supermajority needed to send it to the states for ratification. The future of the amendment would depend on the 1864 election.

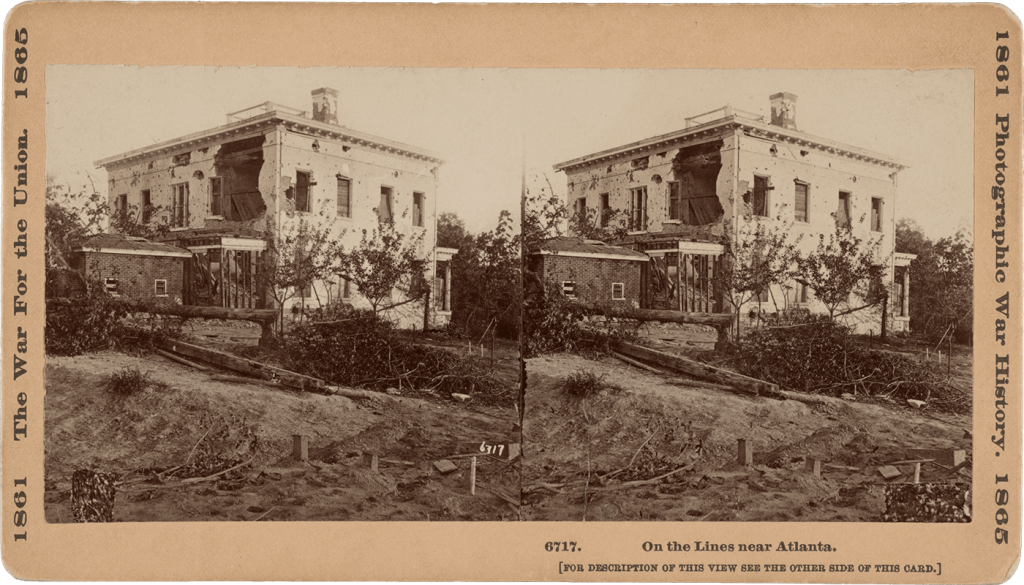

September 2, 1864

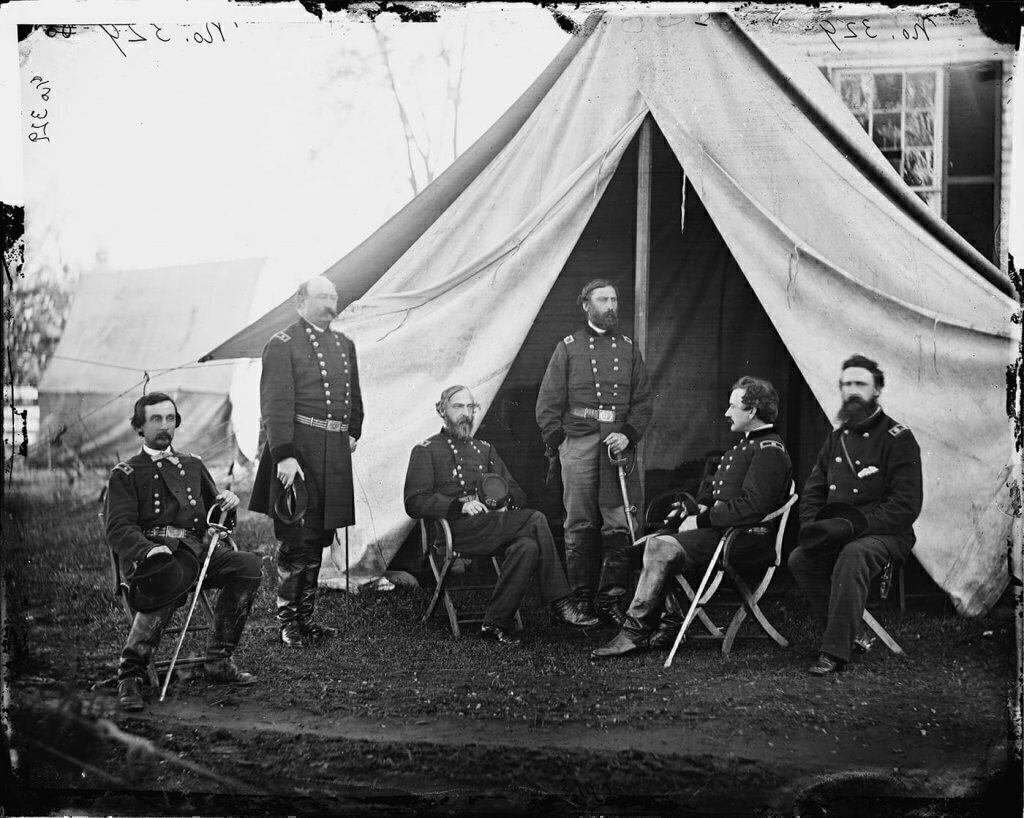

The fall of Atlanta was a key victory for Lincoln and the Union. Lincoln had worried that he might lose the election, but this battlefield victory helped ensure that he would win a second term.

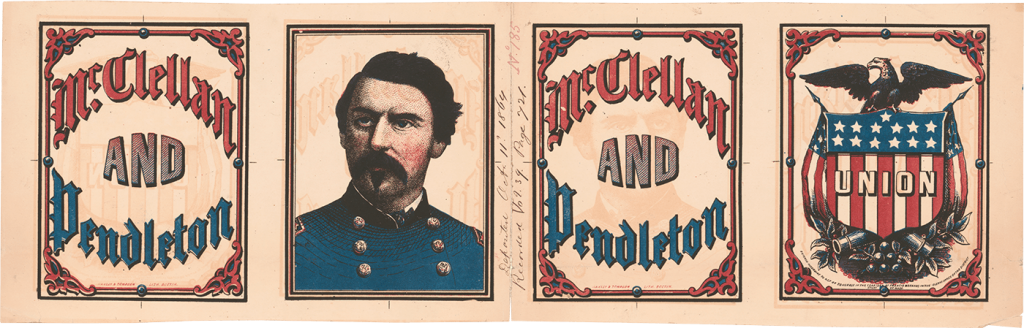

November 8, 1864

The nation held a presidential election during the war. Lincoln defeated George McClellan, his former top general. Many soldiers were able to vote, and they voted overwhelmingly for Lincoln. Republicans also gained seats in Congress, putting them in a strong position to pass the amendment. The key question was whether the “lame-duck” Congress would act.

The lame-duck House revived the debate over the abolition amendment passed by the Senate. The composition of the House had not changed, but Lincoln's reelection, battlefield victories, and Republican gains in Congress contributed to renewed interest in passing the amendment.

January 31, 1865

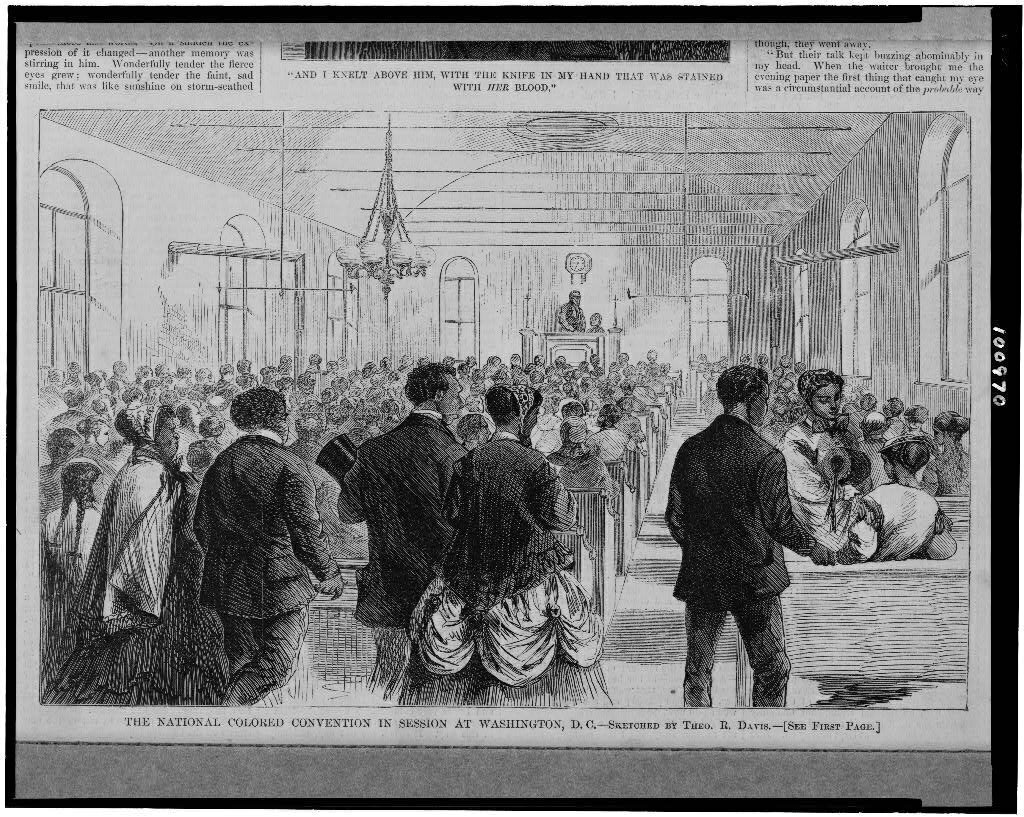

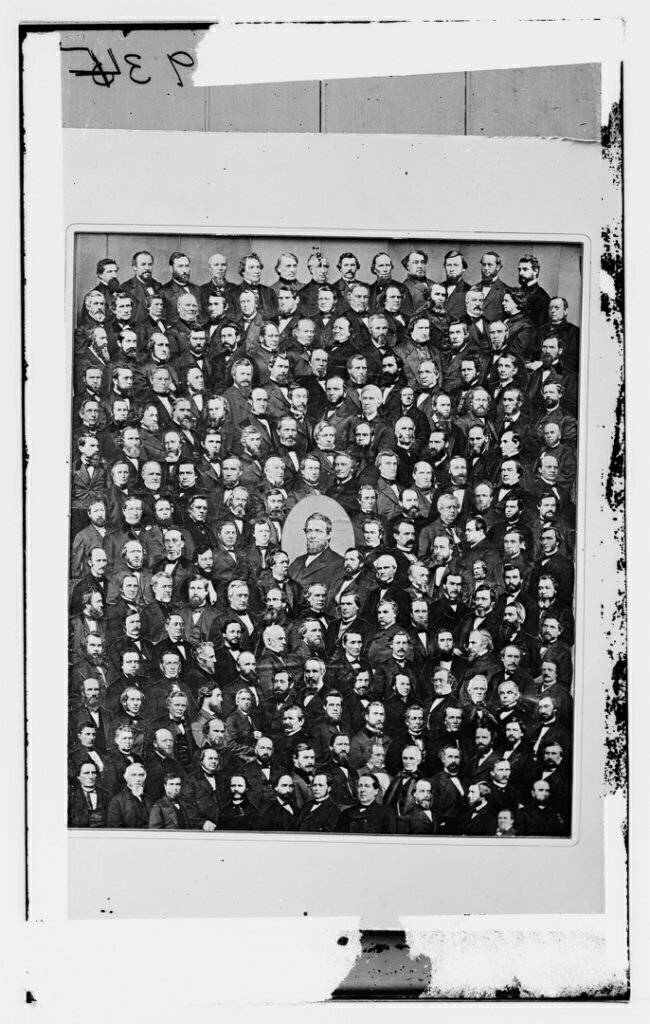

By passing the 13th Amendment, the Reconstruction Republicans achieved something that would have been unimaginable before the Civil War—immediate, uncompensated emancipation. The Senate passed the amendment in April 1864 (38-6), but it failed in the House that June. The House later passed it (119-56), and it was sent to the states for ratification. Upon its adoption, all enslaved persons were freed, and their former owners were not entitled to any compensation.

January 31, 1865

38th Congress

Final Amendment

Section One

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, This text took dead aim at the institution of slavery. Congress debated whether the amendment should just target slavery (itself a massive change) or also include an explicit commitment to equality. Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts pushed for broader language around equality, but the final amendment focused only on slavery's abolition. except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, The amendment barred slavery “except as a punishment for crime”—language that was derived from the 1787 Northwest Ordinance. Sen. Charles Sumner attacked this language during the congressional debates. The provision became more controversial over time, as many Southern states punished African Americans disproportionately under criminal law. shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

This text made it clear that slavery was abolished everywhere within the United States and any territory it controlled. Before the Civil War, most Americans—including those who opposed slavery—agreed that the Constitution gave states control and allowed slavery to continue where it existed. Section Two

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. This section specifically granted Congress the authority to enforce slavery's abolition. It became a model that future amendments would follow. Since the original Constitution set up a national government of limited powers, the 13th Amendment was the first major attempt to expand these powers.

January 31, 1865

38th Congress

Final Amendment

Section One

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, This text took dead aim at the institution of slavery. Congress debated whether the amendment should just target slavery (itself a massive change) or also include an explicit commitment to equality. Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts pushed for broader language around equality, but the final amendment focused only on slavery's abolition. except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, The amendment barred slavery “except as a punishment for crime”—language that was derived from the 1787 Northwest Ordinance. Sen. Charles Sumner attacked this language during the congressional debates. The provision became more controversial over time, as many Southern states punished African Americans disproportionately under criminal law. shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

This text made it clear that slavery was abolished everywhere within the United States and any territory it controlled. Before the Civil War, most Americans—including those who opposed slavery—agreed that the Constitution gave states control and allowed slavery to continue where it existed. Section Two

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. This section specifically granted Congress the authority to enforce slavery's abolition. It became a model that future amendments would follow. Since the original Constitution set up a national government of limited powers, the 13th Amendment was the first major attempt to expand these powers.